In the previous post, I discussed cladistics, the new way of classifying living things based on their position in the tree of life, and mentioned some of the difficulties that arise when trying to adapt the previous classification system, based on the taxonomic tree and Linnaeus's classic categories—kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species—to cladistics.

There are more difficulties. For example, let's consider the concept of kingdom, Linnaeus's highest taxonomic category. Traditionally, living things were divided into two kingdoms: animals and plants. These two kingdoms were clearly separate, with very different characteristics. Thus, animals were defined as organic beings that live, feel, and move by their own impulse, while the plant kingdom were beings that live but do not feel and do not move. It was acknowledged that these definitions were imperfect, because there were exceptions, such as sponges, which barely move but are animals, and some plants, like mimosas, which seem to sense certain stimuli and move in response.

The first serious problem arose with the discovery

of microorganisms. Initially, attempts were made to fit them into the previous

system, dividing them into unicellular animals (Protozoa) and unicellular plants (Protophyta). But in the microscopic world, the separation

between animals and plants becomes blurred, so in the mid-20th century, a third

kingdom was added to the two previous ones: the protists, which encompassed all unicellular organisms, from

which plants and animals would have evolved.

Shortly afterward, biologists concluded that the

plant kingdom should be divided into two: on the one hand, fungi (heterotrophic

organisms lacking chlorophyll, leaves, and roots, which reproduce by spores and

live parasitically, in symbiosis, or on decaying organic matter). On the other hand, all other plants, the Metaphyta (autotrophic

and photosynthetic organisms whose cells have walls composed primarily of

cellulose, and which lack the ability to move).

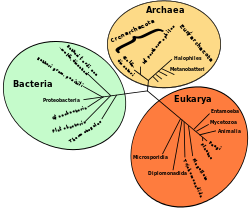

Around 1980, the protist kingdom was divided into three: bacteria, archaea, and unicellular eukaryotes. We thus had a total of six kingdoms, which were further grouped into two categories above the kingdoms, called empires or domains. The classification was as follows:

·

Empire of prokaryotes, cells without a nucleus.

o Kingdom of

Bacteria

o Kingdom of

Archaea

·

Empire of eukaryotes, cells with a nucleus.

o Kingdom of

eukaryotic protista

o Kingdom of

Plants or Metaphyta

o Kingdom of

Fungi

o Kingdom of Animals or Metazoa

It seemed that the

matter was settled. But with the arrival of cladistics, which insists that every biological group

must be linked to all its descendants, things got complicated.

·

On

the one hand, eukaryotes descend from prokaryotes, so their kingdom should be

included within them.

·

On

the one hand, eukaryotes descend from prokaryotes, so their kingdom should be

included within them.

·

On

the other hand, eukaryotes descended through symbiosis from bacteria and

archaea (a bacterium was engulfed by an archaeon, and instead of being digested,

it was incorporated and transformed into a mitochondrion). How does that fit

into the cladistic classification?

· Finally, fungi, and probably plants as well, would have to be divided into several kingdoms because they are polyphyletic, meaning that they do not descend from a single ancestor, but from several earlier groups on the tree of life, and therefore do not constitute a clade.

The conclusion is that, of the six kingdoms

recognized in biological classifications, only one (animals) would be a true

clade.

An additional problem is this: some biologists,

staunch proponents of cladistic classification, argue that if we decide to call

unicellular eukaryotes (for example) a kingdom, then all the prokaryotic

branches that diverged from the ancestors of eukaryotes before the emergence of

eukaryotes and gave rise to independent branches of the tree of life should

also be considered kingdoms. There would thus be more than 50 kingdoms of

living beings, almost all unicellular prokaryotes, some of them with few known

species. Such a classification would not be very useful. Therefore, for

practical purposes, strict cladistic rules are not usually applied at the

kingdom level.

Finally, some biologists believe that humans should

be considered a kingdom of nature, since our species has given rise to a new

type of evolution—cultural evolution—with rules similar to, but subtly different from,

those of biological evolution. I discussed this in one

of the older posts in this blog.

Thematic Thread on Evolution: Previous Next

Manuel Alfonseca

No comments:

Post a Comment