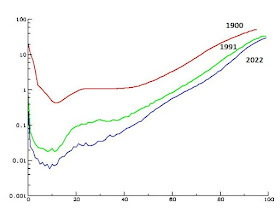

Almost eight years ago I wrote a post on this topic in this blog, which contained a figure that I built starting from data provided by the Spanish Institute of Statistics, which showed mortality data for Spain in three different years: 1900, 1991 and 2013. The three curves in the figure represent the percentage of people who have reached a certain age and will die during the next year. I’m showing here an equivalent figure, with updated data that correspond to the years 1900, 1991 and 2022, as we now have more recent data.

As I said then, the figure shows that medical advances have reduced mortality, especially at the beginning and the end of life, but their effects are little noticeable for people between 20 and 40 years old. The mortality curve, which in 1900 was U-shaped, is approaching an inverted L, with a very low rate for almost all of life and a fairly abrupt rise after age 80.

The Spanish data

end at age 100, for after that age there are so few people alive that no

significant statistical consequences can be deduced. In any case, the curve shows

that in 1900 one out of every two centenarians died the following year, but in

2022 the number is one out of every three. This seems to indicate that human

longevity has not changed in millennia. There always have been

centenarians, and there seems to be a maximum limit for the

length of our life, approximately equal to 120 years.

Reading the book The Long and the Short of It: The Science of Lifespan and Aging, by Jonathan Silvertown (2013, University of Chicago Press), has shown me that the curve in the previous figure is even more useful than it seems at first glance. Silvertown states that, if we make the vertical axis logarithmic, what we get is the aging curve for humans. Let's see how the curves look when this change is applied:

These are the

consequences that can be drawn from this change in our point of view:

•

From 20

to 40 years old we age little. In 1900

the mortality curve was almost horizontal. Now it is growing, but at 40 is

still ten times lower than in 1900.

•

Since the

age of 40, the logarithmic mortality curve grows almost linearly, although the distance between the curves decreases

as we approach age 100. This is why Silvertown claims that the curve, shown

this way, represents aging.

The conclusion is

that medical advances have delayed our aging, without modifying longevity.

Consequently, we cannot expect life expectancy to continue increasing as until

now, unless longevity can be increased, which remains to be seen, since so far,

no progress has been made in this field. In fact, a stagnation in life

expectancy was observed in the United States even before the COVID-19 pandemic,

which marked a setback almost everywhere in the world.

Silvertown also

mentions some studies carried out with the few supercentenarians

(over 110 years old) living now in the world. Their number is assumed to be

about 400, although only 45 are known with certainty. At first glance, it seems

that the increase in mortality stops upon reaching that age, at a value

approximately equal to 50%, which coincidentally was what it had at age 100 in

1900. This means that there is a maximum mortality of 50%: if that value is

reached, mortality no longer increases.

Anyway, assume

that there were 400 people aged 110. Their mortality rate is so high that only

200 would reach 111; of these, 100 would turn 112; 50, 113; 25, 114; 12, 115;

6, 116; 3, 117; 1 or 2, 118; 1, 119; and one or none, 120. Which fits with the

idea, expressed above, that our longevity does not exceed 120 years.

Finally, note that

the mortality curve is currently still U-shaped, as in 1900, although such as

it is usually shown, this is not noticeable. Between 15 and 20% of human beings

die before being born, because they are killed in

induced abortions. This is quite similar to the number of

children who died in 1900 for natural causes during their first year of life. Statistically

the situation is similar, ethically much less so.

Thematic thread on Immortality: Preceding Next

Manuel Alfonseca

No comments:

Post a Comment